How do directors and officers use risk appetite statements to oversee non-financial risk in their companies?

Boards are often cited as having two fundamental functions – to set an organisation’s strategy and its risk appetite.

An organisation’s risk appetite is the amount of risk it is willing to accept in pursuing its strategic objectives. This sets the parameters within which management is expected to operate.

It is good practice for boards of all large listed companies to establish a board-approved risk appetite, in accordance with the ASX Corporate Governance Council’s Corporate Governance Principles and Recommendations [21], and metrics for measuring compliance with that appetite. Twelve per cent of ASX 100 companies are subject to APRA regulation and therefore are required to have a board-approved RAS.[22] All companies subject to this review had a board-approved RAS.

Overall, we observed that boards’ stated compliance risk appetite did not appear to reflect their actual risk appetite, with companies consistently operating outside their appetite. This was not confined to compliance risk, but was typical of non-financial risks generally, which in some companies we observed to be at levels outside appetite for significant periods of time when compared to financial risk. Metrics that were supposed to measure where the company was sitting against its risk appetite did not provide a representative view of the level of risk the company was exposed to. Reporting on non-financial risk did not always align with the metrics in the RAS, reducing boards’ visibility of how the company was tracking against its risk appetite.

In general, we also observed that companies’ risk appetite and metrics were less mature for non-financial risks than for financial risks, where metrics were more granular and comprehensive.

This chapter contains ASIC’s observations about how boards used RASs to oversee and monitor non-financial risk, particularly compliance risk.

What role can RASs play in assisting boards to oversee non-financial risk?

Directors of large, complex companies are charged with the substantial role of overseeing risk management. Used properly, a RAS can be an important tool to assist in this task. A sophisticated RAS enables the board to:

- communicate the desired risk tolerance for specific risks to the company

- monitor and measure how the company is operating against its stated appetite for a particular risk

- mobilise resources and strategies to return the company to within appetite where reporting indicates that it is operating outside appetite.

Effective oversight of risk in large, complex companies is a multi-faceted exercise, requiring analysis, input and reporting from a number of sources. The RAS is only one of these sources; however, it can provide the board with critical insight into the status of key risk areas.

To be an effective tool to oversee risk, a RAS must:

- clearly articulate the level of risk the board is willing to accept and its tolerance regarding that risk

- have metrics that are sufficiently representative, to enable the board to measure where the company is operating against risk appetite and tolerance.

There must also be:

- meaningful management reporting to the board on risk appetite metrics

- a board that holds management accountable, when the company operates outside risk appetite.

General features of RASs reviewed

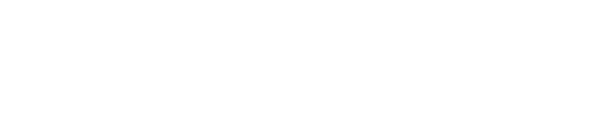

All seven companies had a board-approved RAS, consistent with being subject to APRA regulation. The infographic (below) sets out the features for compliance risk in each organisation’s RAS.

Six of the seven companies set out their compliance risk appetite and included metrics to measure the level of compliance risk they were exposed to. Some companies’ RASs included markers to indicate to the board when they were approaching appetite.

For example, one company that sought to measure when it was approaching appetite limits used an ‘early warning’ level. It also had an ‘intervention’ level, which indicated when it was outside appetite. An early warning was reported as ‘amber’ and meant that a ‘discussion point’ had been reached. An intervention was reported as ‘red’ and meant that a point had been reached where action was required to return to within appetite. This two-stage process appeared to provide meaningful indicators of the actions the board and management were required to take at the different risk levels.

It was concerning that one company did not include compliance risk appetite in its RAS, stating it was ‘not applicable’ for the listed entity, and rather relied on the RASs of its subsidiaries to articulate this risk (although it did not appear to adopt this approach for financial risks). This raises a number of issues:

- It suggests that the board had not consciously considered a specific risk appetite for the conduct of that company (even though it had distinct compliance risks as the result of being a listed entity as well as being the parent of various operating subsidiaries).

- The RAS failed to make clear to management what level of compliance risk the board was willing to accept.

- The board’s failure to articulate its compliance risk appetite meant there was a lack of board-approved metrics for measuring compliance risk exposure across the organisation.

- The board received reports on what management determined was relevant, rather than reports aligned to metrics and its appetite for compliance risk.

- The board did not have a standard against which to hold itself and management accountable for acceptable levels of risk.

Features of the RAS – compliance risk

1 Boards need to hold management to account when companies are operating outside appetite

Our review indicated that all too often management operated outside appetite in relation to compliance risk, and non-financial risk more generally, for extended periods.

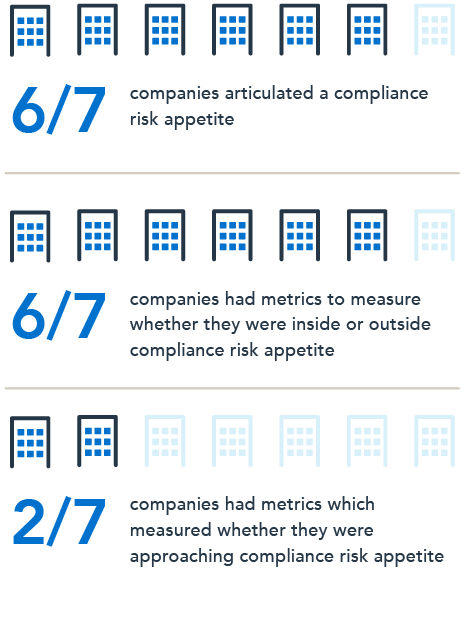

For several companies, it was the norm – not the exception – to operate outside risk appetite for non-financial risk. This is in stark contrast to the position for financial risk, as illustrated in the following diagrams. They contrast two companies’ compliance with their non-financial risk appetites against their financial risk appetites.

Company A – financial risk vs non-financial risk (2017–18)

The infographic shows that the company was outside appetite or approaching appetite for non-financial risks for the 24-month period of the review. By contrast, no financial risks were outside appetite or approaching appetite during this period. While the minutes demonstrated instances of the BRC engaging (in varying degrees) with specific compliance issues, there was no clear evidence in the minutes that the BRC actively sought to urgently return the company into appetite for a sustainable period. We observed issues being addressed as they arose, rather than the board stepping back and considering compliance risk exposure holistically and prioritising the resolution of root causes of appetite breaches. The practical implication of this was that operating outside of appetite for non-financial risk was tacitly accepted in this organisation.

Company B – operating outside appetite or approaching appetite – financial risk vs non-financial risk as at September 2018

The chart above shows another company in which 62% of non-financial risk metrics were outside appetite or approaching appetite, while only 6% of financial risk metrics were outside appetite or approaching appetite. In this organisation, one non-financial risk remained outside appetite for 30 consecutive months, while another moved inside and outside appetite over 30 consecutive months. This raises a question about whether the company was addressing the fundamental or root causes of the relevant risk, and suggests tacit acceptance by the board of operating outside of appetite for these non-financial risks.

Better practice |

Active stewardship requires the board to hold management to account when a company operates outside the board’s stated risk appetite.

The board cannot simply express its disappointment at a risk staying outside appetite for a stated period. It must do more to quickly return the company to within appetite. This includes challenging the actions and timeframes within which management proposes to resolve the issue. Prioritisation and slippage should be monitored and accounted for.

In the absence of tangible and timely plans to return to within appetite, boards should consider whether management needs to cease practices that are causing companies to be outside appetite.

Many companies we interviewed acknowledged they were operating outside appetite for an extensive period, and that it would take some time to return to within appetite. However, one company stated that where it identified it would be outside appetite for a lengthy period, it would change the way it provided certain products and services.

Returning a company to within its risk appetite can be resource-intensive. Several companies noted that the main barrier was finding the right expertise in the market to address the issues. Boards must adapt to their operating environment – where there is a shortage of necessary expertise, they must consider whether current operations should change in light of the heightened risk.

Boards should also require management to undertake root cause analysis, or thematic analysis, to identify underlying causes of recurring breaches of appetite. This is imperative where seemingly distinctive compliance events continue to cause the company to operate outside appetite (or dip in and out of appetite). The board should proactively seek this analysis from management. During our review, we saw sporadic evidence of boards requesting root cause analysis or ‘deep dives’; however, this should occur as a matter of course to help deal with recurrent issues.

Where required structural or long-term solutions are being implemented, the board and management should concurrently consider flexible short-term solutions as a priority to ensure they are operating within board-approved appetite during this time. These could include engaging external resources (e.g. professional services firms) or reviewing the stated risk appetite, rather than simply accepting that they will be operating outside appetite for a long period without appropriate mitigants.

Boards need to ask themselves:

|

Should we default to the position that the company should be operating within the board’s stated appetite in the ordinary course of business? When we fall outside appetite, are we requiring management to do everything within their power to return the company to within appetite, or otherwise cease activities that place it outside appetite? |

If the answer to either question is ‘no’, the board is likely to be seen to be tacitly accepting a higher risk appetite for its company and should consider its own accountability. This tacit acceptance in stark contrast to the company’s stated risk appetite may undermine trust and credibility in the company’s commitment to governance in this area.

2 The full board must engage with the RAS for it to be an effective oversight tool

Setting risk appetite is a fundamental board function. Therefore, it requires full board engagement.

We saw that in one organisation, the BRC, with only a subset of non-executive directors, approved the RAS, instead of the full board approving it at a board meeting. If only a subset of directors formally approves a RAS, it affects the ability of all directors to engage with the details in the RAS and oversee risk management.[23]

Our review also identified board members in two companies who couldn’t explain the metrics accompanying the compliance risk appetite in the RAS, or who had an inconsistent understanding of some metrics, having not engaged with the details in the RAS.

Better practice |

A Financial Stability Board report[24] found that when a board approves a RAS – rather than simply ‘receiving’ or ‘noting’ it – board members have a greater understanding of the risk appetite. It follows that boards that actively engage in the approval process – rather than treating it as a box-ticking exercise – have a greater understanding of their risk appetite. The board and BRC minutes of three companies reflected some level of active engagement with the content of the RAS.

The level of board engagement with the RAS also sends a strong message to management that the board considers the RAS to be important. Lack of engagement diminishes the likelihood of effectively using the RAS to oversee risk. Boards using a RAS as a key oversight tool must ensure that it is up to date and dynamic, and reflects their appetite.

Directors should ask themselves:

|

Do I understand why our compliance risk appetite has been articulated in the way it has, and why certain metrics have been chosen (to the exclusion of others) to measure compliance risk? |

Directors should also ask themselves a similar question in relation to all non-financial risks covered by their RAS.

3 Risk appetite needs to be clearly expressed, reflecting actual appetite

A RAS must clearly express the board’s appetite for the level of risk it is willing for the company to accept.

The RASs we reviewed articulated the compliance risk appetite in a variety of ways. The following infographic maps out those approaches.

How did companies articulate their compliance risk appetite?

The risk appetites of several companies did not appear to match their actual tolerance levels. This was shown by these companies consistently operating outside their boards’ stated risk appetite.

Some of these companies’ RASs made statements of full regulatory compliance. While adopting these types of aspirational statements sends a message to staff, doing so without reinforcing them through strong accountability and consequences significantly undermines the effect of the statement.

Where the company is aware that the statement bears no resemblance to its actual risk position – either because it has operated outside appetite for some time or knows it has never achieved that level of compliance – it can confuse or even mislead employees and third parties, including regulators, that receive the RAS.

Better practice |

In our discussions, many companies acknowledged the challenges of articulating their compliance risk appetite. But few expressed an urgent need to clarify their appetite.

We think boards can do more to express their appetite in a way that is meaningful and aligns with their actual appetite. Compliance with legal and regulatory obligations must be a high priority for boards.

Another useful aspect of many of the compliance risk appetite statements we observed was the addition of statements describing the companies’ expectations when non-compliance did occur – for example, the expected process for identifying, escalating and remediating breaches.

Boards should ask themselves:

|

Does our stated compliance risk appetite reflect our actual appetite? If not, what is the purpose of stating the appetite in this way and how will it help us oversee this type of risk in practice? |

4 Metrics should be a proxy for the actual risk position to enable meaningful monitoring of appetite

The RASs we saw used a variety of metrics to help the company monitor compliance risk.

The metrics we observed for compliance risk often measured discrete issues or areas of compliance, rather than providing insight into the broader compliance behaviour of the organisation. This seems problematic, given that most risk appetites were described in terms of the broader compliance of the organisation.

Many companies’ metrics focused on breaches of specific laws or regulations to measure compliance risk. However, relying on such metrics focuses on lagging indicators of compliance, rather than leading indicators of compliance risk exposure.

In some instances, the reliability of certain metrics was also in debate. For example, one entity had a metric for compliance risk that measured compliance with internal controls. The Chief Risk Officer (CRO) questioned the accuracy of the metric and suggested it was going to be abandoned. In contrast, when separately questioned about the metric, the BRC Chair stood by its effectiveness and suggested no plans were in place to abandon it.

Better practice |

Boards need to select and develop metrics that are representative of the risk they are measuring. Increasing the number of metrics does not necessarily provide the solution, though boards need to consider whether their metrics are sufficiently representative to ‘cover the field’.

Boards should ask themselves:

|

Are the metrics we have approved sufficiently representative to provide a picture of what we are trying to measure across the organisation? |

5 Metrics for measuring risk exposure should align with the stated risk appetite

A number of companies set their compliance risk appetite with reference to how breaches occurred – for example, they expressed zero tolerance for breaches that were deliberate, intentional or negligent. However, the metrics adopted to measure compliance risk largely did not measure how breaches occurred, focusing instead on the nature of breaches.

One company that stated it had no appetite for ‘deliberate, material or notable systemic breaches’ had a metric to identify material breaches that had occurred, but no metrics to determine whether there were any deliberate or notable systemic breaches. The inability to monitor whether breaches are a result of systemic issues significantly limits effective oversight.

It is also unclear whether a causal appetite rather than an outcome-focused appetite correctly articulates the desired outcome of a well-designed and well-executed risk management framework.

Better practice |

Well-developed compliance risk metrics should enable a company to measure how it is complying with its appetite. If a company is measuring its compliance risk appetite by referring to how breaches occurred, it should try and measure that. And the board should still require metrics that facilitate insights into the organisation’s overall level of compliance, by providing a representative picture of risk exposure.

Similarly, boards should also be able to access information to identify systemic issues and perform root cause analysis.

Boards should ask themselves:

|

Do our metrics allow us to measure performance against our articulated appetite? |

6 Metrics should include leading and lagging indicators

Most of the metrics we observed were lagging indicators, measuring breaches of the law that had already occurred.

We saw evidence of some companies attempting to use leading indicators to create early warning systems or identify rising risk levels within the business. For example, we observed leading indicators measuring the number of reopened internal audit issues, or breaches of internal policies as a precursor to breaches of the law. However, these were not as prevalent as lagging indicators.

While using leading indicators in metrics is better than just measuring actual regulatory breaches, the measures being adopted appeared to need further development before they could comprehensively identify when an entity was approaching its risk tolerance limit. Well-developed leading indicators also provide a representative picture of rising risk levels.

Better practice |

Boards should aim to include leading indicators in metrics that raise an early warning for rising risk levels. This would enable boards to require management to act early to avoid breaching a particular tolerance.

Using leading indicators is a well-developed practice for measuring safety risk outside the financial services sector, where the focus has shifted from actual incidents to ‘near misses’. There appears to be more scope for using leading indicators in relation to other non-financial risks such as compliance risk.

Boards should ask themselves:

|

Are we measuring non-financial risk in a way that provides us with early warnings of rising risk levels? |

7 Boards should consider if metrics for a non‑financial risk is comparable to those for other risks

Overall, our review indicated that metrics for financial risk were usually more specific, granular and quantitative, compared to non-financial risk metrics. Financial risk metrics were generally more consistent across the companies reviewed (with particular consistency across the banking institutions), whereas non-financial risk metrics varied much more significantly across the sample.

In one company we observed, metrics for one financial risk were broken down into portfolios, industries and jurisdictions, with each group having a number of quantitative metrics that included a trigger level and a limit. By contrast, compliance risk had just three metrics: the number of new, significant and reportable breaches of law; the number of breaches of specific policies; and one internal compliance measure. Only two metrics had both a trigger and a limit (the third had only a limit).

Another company used 88 metrics to measure financial risks and 14 metrics to measure non-financial risks. While having more metrics does not necessarily translate to better monitoring, this company measured financial risk by jurisdiction, product type and subsidiary owner. By contrast, non-financial risks were commonly only measured according to group-wide total occurrence.

Better practice |

Boards need to consider the impact that metrics have on the depth of analysis for non-financial risks. Metrics should provide insight into broader compliance behaviour. Boards should recognise that ‘what gets measured gets managed’.

Boards should reflect on how their metrics for compliance risks and other non-financial risks compare to metrics used to measure more mature non-financial risks such as workplace health and safety in mining and construction companies.

Boards should ask themselves:

|

When we fall outside appetite, are we requiring management to do everything within their power to return the company to appetite, or otherwise cease activities that place it outside appetite? |

Metrics should provide insight into broader compliance behaviours. Boards should recognise that ‘what gets measured gets managed’.

8 Reporting to the board should be aligned with risk appetite and metrics

Management reporting to the board about where the company sits in relation to risk appetite is only one aspect of risk reporting, but it is an important one. It determines the usefulness of the RAS as a risk oversight tool.

If management does not report to the board against the metrics in the RAS, the board cannot tell whether the company is operating inside or outside its risk appetite.

Of the six companies we observed that included compliance risk metrics in their RASs, one company’s CRO report did not align compliance risk reporting with the metrics in the RAS. Rather, it reported against other metrics or measurements, creating a disconnect between the RAS and risk reporting. This disconnect may have occurred due to shortcomings of the relevant RAS metrics. In another company, non-financial risk metrics were not reported in the headline CRO report, but instead in the Compliance Officer’s report. In contrast, financial risk metrics were included in the headline CRO report.

In other companies, management risk reporting better aligned with the metrics in the RASs, including reporting to the board against the company’s stated appetite. The degree to which this alignment translated into effective reporting depended on those metrics being meaningful.

Better practice |

Management should report to the board with meaningful data that shows how the company is operating compared to its risk appetite. By aligning its reporting, it provides a clear view of the level of risk the company is accepting, compared to what the board is comfortable with.

One organisation’s compliance reports were particularly useful in that they showed how it was operating against its compliance risk appetite, including risk mapping that identified deteriorating trends in certain compliance categories that could increase the compliance risk. This gave the BRC advance warning of potential increases in compliance risk levels.

Risk reporting at the management committee level that is aligned to the RAS can also help the board’s oversight function. It can do this by engaging management on the board’s appetite for non-financial risk, and enhancing the quality of management reporting to the board.

We saw some evidence of this in one company. This could be further enhanced by ensuring that management has data on who is responsible and what needs to be done to return the company to appetite, enabling it to feed this information to the board.

Board members should ask themselves:

|

Does management report to the board against the metrics in the RAS? Do management committees receive reporting against the metrics in the RAS? |

International trends |

Companies around the globe face similar challenges in expressing measurable appetites and metrics for non-financial risks, and aligning business and risk reporting. International trends show that efforts are being made to overcome these challenges and use risk appetite as a proactive risk management tool.

Internationally, we have observed differing practices regarding the structure of operational and compliance risk functions in businesses. While some companies in the United Kingdom have brought their operational and compliance risk functions together, some in Europe have separated them. The European Banking Authority’s (EBA’s) governance guidelines[25] encourage ensuring appropriate authority and stature to the heads of internal risk and compliance functions. For some large and complex institutions, this is occurring through separating risk and compliance.

Companies are also adopting more forward-looking indicators and automated data aggregation to move towards real-time dashboard reporting that shows risk compared to appetite. They are also using data mining and analytics to help identify trends and undertake root cause analysis.

Some companies are also seeking to be explicit about who is accountable for each type of non-financial risk, increasing the accountability of the business (as opposed to risk and compliance functions) for compliance risk. For example, in the United Kingdom, the Senior Managers and Certification Regime, which is similar to the Banking Executive Accountability Regime, has increased the focus on responsibilities and accountabilities. This is driving boards to proactively manage risk exposures.

21 In the third edition, this appeared in the commentary. In the fourth edition it appears in recommendation 7.2. The fourth edition’s effective date is the first full financial year beginning on or after 1 January 2020.

22 See APRA Prudential Standards CPS 220 and SPS 220. APRA-regulated registrable superannuation entities (RSEs) are required to have a board-approved RAS at RSE level.

23 See Attachment A at page 7 for discussion regarding non-executive directors’understanding of operational issues in the business

24 Financial Stability Board, Principles for an Effective Risk Appetite Framework, 2013.

25 EBA Guidelines on Internal Governance, EBA/GL/2017/11.