Are boards getting the right information to enable them to oversee and monitor non-financial risk management?

Effective oversight is informed oversight. Directors need sufficient information to hold management to account and discharge their stewardship over the company’s assets.

This does not require that every piece of information be provided to directors. To adequately oversee and monitor non-financial risk, boards need management to provide timely and accurate information that focuses on material non-financial risks. Where the information lacks these qualities, poor oversight, accountability and decision making are inevitable.

Responsibility for the quality and nature of reporting to directors should not solely lie at the feet of management or the company secretary. Directors need to actively engage with this process. They should ensure their organisation has systems and processes to get them the right information needed to perform their oversight and monitoring functions.

This section contains ASIC’s observations on information flows:

- from management to the board

- between board members

- through committees.

Our review considered verbal and written communication, focusing on whether boards are getting the right information to enable informed decision making on non-financial risks.

Overall, we observed that:

- material non-financial risk information was often buried in dense, voluminous board packs

- it was difficult to identify the materiality of key non-financial risks in information being presented to the board

- undocumented board sessions and informal meetings between directors had the potential to create asymmetric information at board level, if not well managed

- board committees needed to do more to ensure that information flows to other committees and to the full board were formalised and conveyed key risk issues to all board members.

1 Material information should not be buried in lengthy board packs or reports

Directors need to have sufficient information to understand the nature and likely impact of material issues facing the company. However, our review indicated that board packs were so dense and voluminous that it was unclear whether their primary purpose was to:

- inform directors in the most effective manner, or

- absolve reporters from exercising judgment as to what information should be omitted.

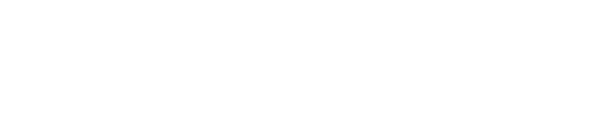

Papers presented to the BRC are a key part of the information flow on non-financial risks from management to the board. The infographic (below) sets out the average number of pages for BRC packs reviewed. It shows that packs presented to BRC meetings averaged just under 300 pages, with one organisation’s papers averaging just over 700 pages.

Average number of pages in a BRC pack

The volume of papers that directors are required to read needs to be considered in the context of the growing trend for directors to attend more committee meetings and the common practice to hold committee meetings and full board meetings on consecutive days.

One Chair, who had been working to reduce the size of board packs, commented that directors had recently received packs for all committees – including the BRC and full board meetings – which totalled 900 pages. Reflecting on this, it was the Chair’s view that the issues could be explained in 130 pages. The length of board papers often far exceeded an organisation’s own guidance and template length.

Better practice |

It is not length itself that is the issue – rather, it is unnecessary length. When directors themselves consider that the information they need could be explained in less than 25% of the volume provided, work needs to be done to ensure concise management reporting that focuses on the key non-financial risks. Directors need to be proactive in requiring management to deliver information in a form that will help them to fulfil their oversight and monitoring mandate.

We do not believe that imposing and enforcing a maximum page limit will solve this issue. But the fact that organisation-specific guidelines are not being enforced suggests that chairs have not been sufficiently engaging with the nature of reporting provided to them.

Boards should ask themselves:

|

Is the breadth and materiality of information that management provides correctly calibrated to help us perform our oversight function? Is the information we receive on non-financial risk of a similar quality to that we receive on financial risk? |

2 Management reporting should have a clear hierarchy for non‑financial risks that prioritises their importance

Directors commented that the information in board packs was dense, making it difficult for non-executive directors to understand its relative impact and importance. Many directors said talking to relevant members of management at a meeting (or in free-flowing discussions outside a meeting) provided useful context. This suggests that information in the papers is inadequate, and that context is needed to accompany the papers.[26]

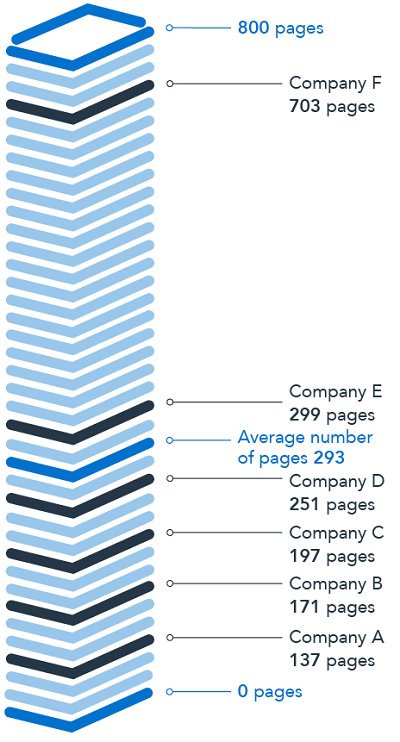

CRO and compliance reports – which are key vehicles for informing the board of material non-financial risks – often did not provide a hierarchy showing the comparative importance of key non-financial risks. CRO reports varied in length and depth of information, and there is scope to more effectively prioritise information. The following infographic shows the average page length of ‘headline’ CRO reports – that is, CRO reports that were designed to highlight key risks, ‘cover the field’ or summarise other risk reports.[27]

Average page length of ‘headline’ CRO reports

One CRO report contained static headings for specific risks and mainly detailed green-rated risks first. This has the effect of starting with ‘good news’, while risks that were over the tolerance limit or at a trigger threshold were reported later.

Other CRO or compliance reports placed key non-financial risk information in appendices to the reports. We observed some reports that cross-referenced other reports or BRC agenda items, but often the links between multiple reports were unclear or not mapped. This creates scope for information overlaps and gaps, and can make it difficult to determine the materiality of an issue across an organisation. Where this occurs, the board has to interpret the possible organisation-wide impact of information presented across numerous documents.

Better practice |

Boards should not have to search through substantial amounts of information to seek out references to material risks. Management should be required to tell them where to look.

An example of better practice was a compliance report that provided detailed commentary on specific risks, in order of greatest to least severe. The Chair of this BRC noted that this prioritisation was a result of conscious board efforts. Historically, reports contained key information, but it was buried and wasn’t being drawn out for the board.

Boards may wish to consider initiatives to improve mapping and synthesis of risk and compliance reports, to ensure they prioritise key non-financial risks. With boards receiving on average 10 to 43 separate papers for each BRC meeting, it is important that they can identify material non-financial risks when reading the reports all together. Summary reports that highlight material issues raised in lengthier reports may also assist the board to prioritise risks.

Boards should ask themselves:

|

Are significant issues receiving sufficient prominence in reports? Does management reporting make it easy to identify the materiality of non-financial risks across the organisation? |

3 Material information should not be lost in undocumented closed sessions

The majority of organisations had ‘closed sessions’ during their BRC meetings, which typically included only non-executive directors, and no management or only the CRO.

There was strong consensus from directors regarding the significant value of these sessions. They allow non-executive directors on boards or committees to question management without managers present, and to discuss highly sensitive information.

However, when these conversations are not recorded in a way that captures the material issues and action items discussed, it can lead to reduced or impaired information flows to the wider board or management who must address the issues raised.

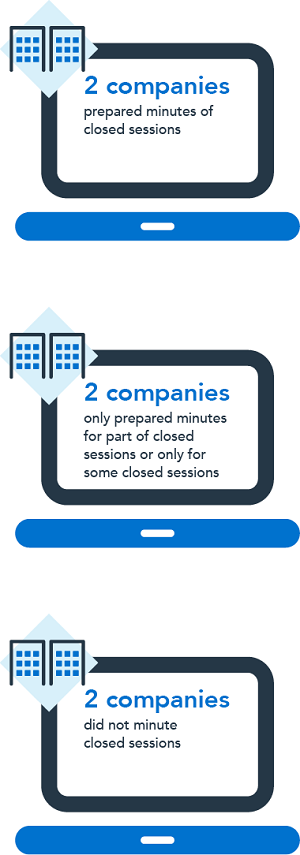

The BRC at six out of seven organisations had closed sessions in 2018. Despite their importance, two-thirds of the six organisations:

- did not record items discussed or actions arising in minutes

- only minuted certain closed sessions, or only certain parts of them.

Where closed sessions were minuted, the minutes did not convey whether material items were discussed, or whether any action items arose.

This meant that board members who were not present had to rely on verbal updates. More concerningly, there was no detailed corporate record of the matters discussed.

Minuting of BRC closed sessions – 2018

Better practice |

Material non-financial risks – indeed, all material issues – and action items arising from closed sessions should be recorded to ensure information flows are not reduced or impaired.

Boards should ask themselves:

|

How are we ensuring that board members not present during closed sessions are informed about material non-financial risks? How are action items coming out of closed sessions recorded and conveyed to the board and management? |

4 Minutes should include key discussion points and reasons for decisions

While it is a legal requirement to record minutes of board and board committee meetings, appropriately detailed minutes are also important for ensuring effective information flows around the board, and from the board to management. In addition, minutes can help boards to demonstrate they have exercised active stewardship and performed their oversight and monitoring functions.

The minutes we reviewed were often brief and formulaic. Generally, they lacked sufficient information about topics discussed or key factors in decision making. For example, none of the six entities minuted BRC closed sessions with appropriate detail.

While we observed better minute-taking practices over the 2018 calendar year, standards could be further improved. For example, we were generally unable to determine the quality of active oversight by board members due to the limited information in minutes.

Better practice |

The Australian Institute of Company Directors and the Governance Institute of Australia have released a joint statement on board minutes[28], setting out key principles for what matters should be recorded. The statement notes that minutes do not have to be a transcript of board meetings; however, they must record the proceedings and resolutions of board meetings (including board committee meetings).[29] Importantly, the joint statement advises organisations to include the key discussion points and reasons for decisions to help demonstrate that directors have discharged their obligations.

In addition, the joint statement notes that while the level of detail to be captured is a judgement call, it is appropriate for minutes to record ‘significant issues raised with management by directors’ as well as action items arising.[30] Recording significant issues raised with management and the actions sought from management will help the board demonstrate where they have exercised genuine oversight.

Boards should review this joint statement against their own minute-taking practices, including for closed sessions, to ask themselves:

|

Do our minutes adequately capture key discussion points, reasons for decisions and significant issues raised with management? |

5 Informal meetings should be conducted in a manner that avoids asymmetric information between board members

Boards receive information from a variety of sources outside formal board meetings and board committee meetings. Many directors commented on the value of discussions at board dinners or during one-on-one or small group meetings before formal board meetings, and insights gained from site visits.

Better practice |

We recognise that boards need to interact in a manner that increases their effectiveness, which includes informal meetings. These meetings are a good forum to gain greater understanding of issues and insights into company operations. Boards need to be mindful however of the risks involved where informal conversations result in decisions or actions being agreed upon absent formal frameworks or without the benefit of the entire board’s views being considered. Boards should implement practices that minimise these risks, such as monitoring the subject of discussions that are not repeated at a formal meeting, and formally recording key decisions and action items.

Boards should ask themselves:

|

How are we ensuring that all directors have the benefit of material information obtained during informal conversations or meetings? |

6 Board committees should ensure the full board is updated on material non‑financial risks in a timely way

We observed that information flowed from the BRC to the full board or other committees in a variety of ways. The table below depicts the combination of methods different organisations used to update the board on BRC matters, including direct reporting from management, minutes and updates provided by the BRC chair.

As the table shows, organisations used a variety of methods to update the board. The methods often complement each other. For example, while minutes often weren’t available to the board for some months, verbal updates at the next meeting (often the next day) helped fill the gap.

However, most methods also had limitations. For example, minutes were brief (we observed that board minutes were often even briefer than BRC minutes) and verbal updates were often allocated only very limited time on the agenda. While verbal updates have some inherent benefits, relying too heavily on verbal updates without any accompanying analysis reduces objective data-driven reporting; therefore, it increases the risk that the presenter will frame the materiality of risks according to their own understanding or bias.

|

CRO attended most or all board meetings |

Written CRO/risk report provided at some or all board meetings |

BRC minutes provided to board meeting |

Verbal update from BRC chair (where not all directors attended BRC) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Organisations with full board membership at BRC |

||||

|

Company A |

|

Limited[31] |

|

|

|

Company B |

|

Limited |

|

|

|

Organisations with all non-executive directors invited to attend BRC (but not all are members) |

||||

|

Company C |

Some |

Limited |

|

|

|

Company D |

|

Limited |

|

|

|

Company E |

|

|

|

|

|

Company F |

Some |

|

||

|

Sub-set of the board are members and attendees at BRC |

||||

|

Company G |

|

|

|

|

Organisations that invited all non-executive directors to attend BRC meetings often appeared to provide less detailed reporting to the full board, assuming that all board members would attend the BRC meetings. This becomes problematic when not all directors attend BRC meetings.

As we note in the section on BRCs, there was an emerging trend toward inviting all directors to BRC meetings, but most companies had not formalised BRC membership for all directors. Therefore, it is possible that the practice of the full board attending in some organisations may subside or reverse. Among organisations that currently invited all non-executive directors to BRC meetings, not all directors attended every meeting.

Better practice |

Where not all directors attend BRC meetings, it would be better practice for the CRO to attend the relevant part of board meetings and present a written CRO or risk report. This will help to ensure directors are aware of material non-financial risks discussed during BRC meetings.

The methods that management and the BRC use to update the full board should work together to inform non-attending directors of material non-financial risks discussed at BRC meetings.

Boards should ask themselves:

|

Are the methods we use to update the full board sufficient to ensure it receives reliable and timely information about material non-financial risks? |

7 Cross‑committee information flow should be formalised

APRA’s inquiry into CBA noted that simply having cross-committee membership was not enough to ensure efficient information flows between board committees.[32] This is particularly relevant for large, complex organisations where numerous issues are likely to arise within those forums, and they need to be formally referred across committees to achieve a whole-of-company perspective.

Despite this, some organisations still appeared to rely on cross-committee membership as a key part of their information flows.

Better practice |

The Chair of one organisation implemented a ‘handover note’ system between committees, which was recorded in committee minutes. This was intended to ensure that important issues did not slip through the cracks as a result of relying on cross-committee memberships. The Chair also noted that this process was very effective for signalling to management the importance of specific issues.

The BRC charter of one organisation mandated sharing information with the Board Audit Committee and other board committees where relevant, while another required that relevant chairs hold meetings, where necessary. Formalising information sharing in this manner may help to introduce more reliable information flows between committees.

Boards should ask themselves:

|

How robust are our processes for cross-committee information sharing? |

8 Boards should explore alternative solutions to enhance information flows

Designing and implementing a system that effectively identifies and escalates issues to the board is clearly complex. All organisations we reviewed were grappling with this challenge – and clearly there is no ‘silver bullet’ solution.

Given the importance of this issue, we encourage organisations to think laterally about how they can improve information flows. In many cases, this may involve enhancing and refining existing processes. While we are not encouraging organisations to introduce new structures or frameworks for the sake of having additional processes, those that address a root cause of the problem can have a positive impact.

We reviewed one organisation’s executive-level non-financial risk committee to determine how it affected information flows to the board. While having management committees that focus on non-financial risk can have benefits, boards need to:

- consider their motivation for establishing such a committee (that is, is it a ‘form over substance’ solution to address poor information flows?)

- consider whether existing structures can deliver the desired outcomes

- ensure that such a committee delivers on the board’s desired goals.

Case study: Executive-level non-financial risk committee

Review

We reviewed the manner in which one executive-level non-financial risk committee helped the board oversee non-financial risks, including through identifying and escalating risks. We considered how the committee shaped information received at the board level, and in turn aided board oversight of non-financial risk.

Key observations

We observed the following:

- The committee appeared to enable informed updates to the board on non-financial risks. It shaped agendas and items for BRC and board meetings, to ensure key issues were addressed.

- Its existence heightened awareness of the materiality of risks, and provided opportunities for management to cascade messages downstream and increase awareness of issues affecting the organisation more widely.

- Business unit updates at committee meetings were largely verbal. This supported free-flowing discussion and reflection on how issues affected other business units. (However, read about the limitations of verbal updates.) Nevertheless, we observed limited consideration of systemic issues or root causes of issues that may have been valuable to the board.

We also observed the following examples of better practice for the executive-level committee:

- Its reporting was aligned to the company’s RAS, which helped management provide the board with meaningful reporting on risk appetite.

- The committee appeared to enable more coordinated thinking around non-financial risks, enabling management to ‘join the dots’. The Chair of the full board said it had helped highlight materiality and context of non-financial risks for the board.

International trends |

The themes we observed in our review were also evident internationally, with entities facing challenges including:

- unfocused and voluminous reporting

- a wide variety of reports on granular risk types, and insufficient streamlining of reporting on non-financial issues.

There is also greater focus on automating non-financial risk reporting, including the use of faster and integrated data aggregation capabilities to enable efficient and timely escalation of issues. Technology and data solutions that achieve this are often referred to as ‘regtech’ or ‘corptech’.

According to a recent Bank of England (BoE) report, 57% of regulated firms that responded to a survey said they were using artificial intelligence applications in their risk management and compliance areas.[33] BoE noted the benefits of such applications but warned of their limitations – human incentives still impacted the quality of the systems, and the transition process was resource-intensive and presented unique risks. These include the need for new skill sets at board and management level.[34] Applications may also unintentionally obscure the root causes of issues, with users being unable to determine whether they need to resolve a systems issue or an organisational issue.[35]

Other corporate governance experts have also warned that new technologies will not solve all corporate governance issues.[36] Accordingly, while technology and data solutions can be useful in assisting organisations to navigate complex problems with issue identification, escalation and information flows, they should not be solely relied upon to solve such issues. Directors also need to be aware of the risks, as with any new technologies.

In another global trend, management-level non-financial risk committees have become increasingly common.[37] One international bank has one or two board members attend management-level non-financial risk committee meetings as a challenge point, and to ensure that the board is aware of emerging issues early.

26 See Attachment A at page 7 for discussion regarding roadblocks to understanding and verifying information provided by management.

27 Based on a review of reports from the second half of 2018. One organisation only recently introduced CRO reports in this format so its average is based on one report.

28 Australian Institute of Company Directors and the Governance Institute of Australia, Joint statement on board minutes – August 2019.

29 Section 251A, Corporations Act.

30 Australian Institute of Company Directors and the Governance Institute of Australia, Joint statement on board minutes – August 2019, page 2.

31 Limited – only some CRO reports were provided to the board meeting (i.e. a report on regulatory breaches, or on certain risks).

33 Managing Machines: the governance of artificial intelligence; speech by James Proudman, Executive Director of UK Deposit Takers Supervision. FCA Conference on Governance in Banking, 4 June 2019.

34 As above.

35 As above.

36 Enriques, L., Corporate Technologies and the Tech Nirvana Fallacy, European Corporate Governance Institute – Law Working Paper No. 457/2019.

37 APRA CBA Inquiry Report; Deutsche Bank in Germany has established a non-financial risk committee at its management board level. Dutch bank ING Group has created a similar committee. To address specific non-financial risks, American organisation Johnson & Johnson has established a management-level triage committee, and US pharmaceutical company Pfizer has a board-level regulatory compliance committee to oversee certain compliance risks.