How do directors and officers use board risk committees – in practice – to oversee non-financial risk in their companies?

Why have a BRC?

BRCs can play a vital role in:

- bringing independent judgement to risks

- focusing the board’s oversight of non-financial risks

- reviewing and debating risk frameworks and appetites

- monitoring compliance with risk tolerances

- monitoring material risks (including emerging risks) through the escalation of significant incidents and breaches

- identifying root causes and trends.

Our review indicated that companies were generally seeking to use BRCs to achieve the above outcomes, but they could be more effective in doing so. This chapter sets out some areas for improvement in governance practices.

The use of BRCs

The ASX Corporate Governance Council’s Corporate Governance Principles and Recommendations encourages all listed companies to have a committee that oversees risk.[38]

As the infographic below demonstrates, 87 of the ASX 100 companies have a board committee that includes risk in its mandate. These committees are a mixture of either standalone risk committees or combined committees (with the most common combination being an audit and risk committee). Of the 24 companies with a dedicated BRC, 12 are required to have a BRC under APRA’s Prudential Standards.[39]

ASX 100 companies and BRCs

Each of the companies we reviewed had a standalone BRC.

Having a standalone risk committee appears to be increasing in prominence internationally – the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s (OECD’s) Corporate Governance Factbook 2019 reports that around one-third of jurisdictions require or recommend that companies have a separate risk committee – this is double the number reported in the 2015 edition of the OECD Corporate Governance Factbook.[40]

ASIC encourages all large listed companies to consider whether creating a dedicated BRC would benefit their long-term interests given:

- the broad mandate and workloads of audit committees

- the ability of risk committees to focus on non-financial and financial risks

- the inherently backward-looking nature of the work of audit committees, compared with the forward-looking nature of risk committees

- the degree to which dedicated risk committees can enhance the focus on risk within companies.

Regardless of whether companies have a standalone or combined risk committee, ASIC encourages all boards that have committees with risk in their mandate to consider revising their practices in light of the observations in this chapter.

1 BRCs need to dedicate enough time to discharging their mandate

BRCs have broad mandates. The charters reviewed set out duties ranging from considering risk frameworks to monitoring the impact of risk events and overseeing how management deals with material risks.

Failures and misconduct arising from lack of oversight of non-financial risk in financial services institutions suggest that greater focus and time needs to be dedicated to these challenges.

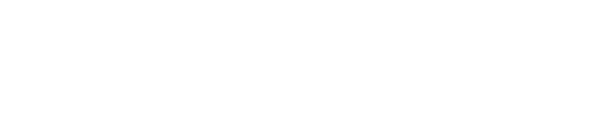

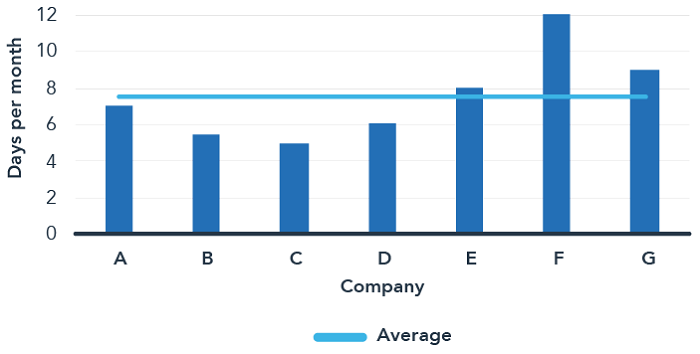

The chart below shows the total annual sitting hours of the BRCs of the companies reviewed.

Given the complexity and scale of these companies, the total hours spent sitting each year seems modest, especially considering the events faced in 2018 (including the Financial Services Royal Commission). Some companies held additional board meetings rather than BRC meetings to deal with ad hoc issues requiring board-level discussion or decisions. But we are still concerned about the limited sitting time of BRCs, considering the breadth of their mandates and the challenges these companies face in relation to overseeing and managing risk.

Despite committees often being referred to as the ‘workhorses’ of boards, the total overall time spent for most companies suggests:

- BRCs are not considering significant risks, which are being dealt with at other venues such as full board meetings, and/or

- BRCs are not being fully utilised to resolve the challenges non-financial risks represent to companies.[41]

Total annual hours for BRC sitting

Estimate of time commitment as a BRC chair and non-executive director – days per month

As the chart above shows, BRC chairs estimated they needed, on average, five to 12 days a month (1.25–3 days a week) to perform their non-executive director and BRC chair roles, with many noting that the workload had increased over recent years.

In providing this average figure, many BRC chairs commented that there were times when the demands were more intense due to company reporting or other requirements. Some stated that at times they were required to be available every day to deal with matters that arose. Many noted that the events of the past 12 months had also led to periods of intense activity.

Given the observations in this report, directors who chair or sit on a BRC need to consider whether they are committing sufficient time to BRC-related duties. Most board members we interviewed held board positions on multiple companies. They need to consider whether the number of positions they hold allows them to adequately discharge their oversight responsibilities, given the size and nature of the companies and their board responsibilities.

Better practice |

Committees dealing with risk need to ensure they give sufficient time to discharging their risk mandate. This includes the need to consider ‘big picture’ framework issues as well as current and future risk positions or significant risk events that emerge.

Directors who chair or sit on a BRC and multiple other boards should ensure they have capacity to attend to their oversight duties not only during ‘business as usual’ periods but also during periods of intense activity.

Boards should ask themselves:

|

Are we dedicating sufficient time to risk issues, including non-financial risks, at the BRC level? |

BRC chairs should also ask themselves:

|

Am I allocating sufficient time to perform my duties as BRC Chair, taking into account the scale and complexity of the company? |

2 BRCs need to meet often enough to oversee material risks in a timely manner

A BRC should not just be a forum to consider the company’s approach to risk at a framework level. It needs to be able to oversee the company’s practices to be satisfied it is following the risk management framework and that the framework is effective.

All BRC charters reviewed by the Taskforce require BRCs to oversee management’s implementation and operation of the risk management framework and risk management strategy. A review of the minutes of some companies’ BRC meetings indicated that the BRCs oversaw current and emerging risks, in addition to risk framework matters.

However, BRCs should ensure they are being made aware of material risks in a timely manner. This helps with identifying trends and leading indicators, to address risks earlier, reduce the severity of the impact if the risk crystallises, and identify root causes.

A BRC that meets quarterly has limited ability to respond to leading indicators in a timely manner or monitor time-sensitive issues. While time-sensitive matters can be dealt with outside the BRC, the BRC should meet with enough regularity to ensure that issues are dealt with promptly.

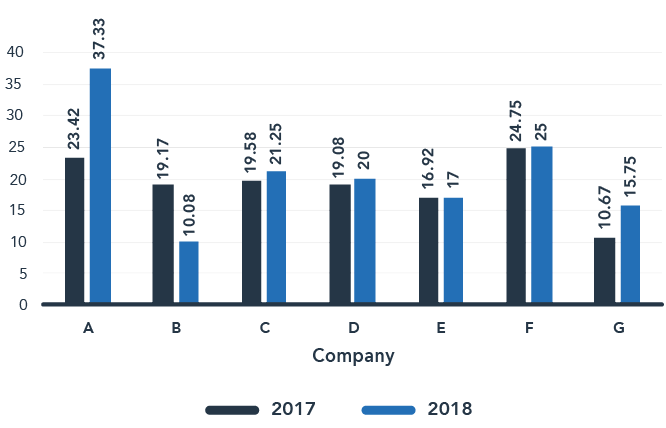

As the chart below shows, the number of BRC meetings each company held varied between four and 12 over 12 months in 2017 and 2018.

Standardised or repetitive items dominated meeting agendas, which were largely set at the beginning of the year. We observed that those companies that held, on average, monthly BRC meetings had agendas that included a wider range of matters that had arisen. In contrast, BRCs that met more infrequently had less varied meeting-to-meeting agenda items.

Number of BRC meetings (annual)

Better practice |

It is important to identify trends or significant risks early. Two companies formalised this in their charters. One gave its BRC a mandate to ‘identify thematic issues that require attention’ and the other required the escalation to the BRC of ‘new, heightened or significantly varying risks in a timely way’. However, BRCs need to ensure this occurs in practice and is not just an aspirational statement in the charter. We saw evidence of one BRC requesting ‘deep dives’ into certain risks, as a form of root cause analysis.

While it is important to have processes for escalating urgent risks, if material risks are routinely addressed outside committee meetings, companies should consider whether the frequency of their BRC meetings is adequate.

Boards should ask themselves:

|

Does the BRC meet often enough to oversee material risks in a timely manner? Does the frequency of our BRC meetings allow for the timely elevation of material risks to the committee? |

3 BRC members need to ensure they are providing informed oversight

Without receiving adequate information, BRCs cannot identify the root causes of issues that arise, nor monitor how the company is tracking against its risk appetite. Information flows between the board, committees and management are discussed here in more detail.

The charter of one BRC we observed states:

The Committee’s principal function is one of supervision, oversight and monitoring. The Committee performs its principal function based on information provided to it by management. Management is responsible for the preparation, presentation and integrity of information provided to the Committee. Without limiting the Committee’s responsibilities, as described in [the] Charter neither the Committee as a committee nor any member of it by virtue of being a member, has the duty to actively seek out activities occurring within the Group that are not compliant with the Group’s policies and procedures, although they have a duty to act promptly if any such activity comes to their attention.

We understand this clause was included to clarify the company’s understanding of the delineation between management and the board, but was to be read in light of other provisions in the charter as well as legal obligations on directors requiring active stewardship. Specifically, it was intended to deal with any expectation that the BRC members would act in the role of management in looking for issues.

However, as drafted, in isolation the clause could be misconstrued as sanctioning BRC members to accept information provided to the committee on face value, without challenging its nature or quality. ASIC understands that this company has not adopted this practice, but including such clauses in charters could be misinterpreted in this way, and does not represent good practice.

Better practice |

Members of the committee must ensure they are providing informed oversight. If the BRC believes management is not giving it adequate information about compliance with the risk management framework, or if it is only receiving ‘good news’, then the BRC has a duty to make enquiries of management and take steps to rectify the information flow. BRCs should ensure that their charter accurately reflects actual practice in relation to informed oversight.

Getting management to undertake root cause or thematic analysis of non-financial risks that continue to arise in the company’s operations demonstrates active stewardship on the part of directors. These enquiries are for the purposes of informing the BRC, not undertaking the role of management.

Boards should ask themselves:

|

Are we receiving the right kind of information to discharge our duties? How are we satisfying ourselves that this is the case? |

4 Boards need to actively engage in decisions and proposals at the BRC level

Active stewardship means directors cannot simply sit back and accept information provided on face value. They cannot, as one director noted, just ’look to them [division head] to tell us if they’re managing their business properly’. Directors should actively probe and analyse information presented by management to test its robustness, and judge the merits of proposals and the adequacy of management actions.

We consider that signs of active oversight include directors:

- requesting further information, analysis or action from management

- asking questions of management

- requesting changes to recommendations or proposals

- rejecting recommendations or proposals

- driving the implementation of changes to address identified failures by management.

Our assessment of the existence of active oversight relied on our review of BRC minutes. These minutes were typically very high-level, so the data below needs to be considered in that light.

We observed from minutes of BRC meetings in 2018 that there were more instances of active oversight of non-financial risk matters than of financial risk matters. This could be explained by the nature of the subject matter, greater focus on these matters recently and a conscious decision to capture these issues in the minutes.

There were signs of active oversight in only 29% of all items that required a decision, and in 32% of ‘non-decision items’.[42] As shown in the infographic below, of the items that needed a decision, the board required management to do further work or implement changes in a higher proportion of cases than for the ‘non-decision items’. The majority of board engagement in relation to ‘non-decision items’ consisted of the BRC asking questions or requesting further information.

BRC challenges

Active oversight requires directors to take action to prevent failures from reoccurring rather than merely expressing concern. In a single board meeting for one company, we observed three separate requests for board ratification due to management’s prior failure to seek board approval at the required time. In each instance, the minutes record that the board ‘expressed concern’ over the failure to seek board approval at the relevant time, yet nevertheless ratified the action. In two of these instances, the board also identified a delay in seeking ratification once the failure had been identified and on one occasion the board merely ‘reiterated the importance of escalating bad news quickly’.

This example demonstrated a lack of active engagement by the board with the very serious issue of an apparent systemic lack of compliance with key internal controls relating to board delegations, as the board did not appear to take ownership of the issue. Instead of the board instigating and driving a review into how their delegations were being managed, the delegates themselves appeared to drive the scope of the internal review into the problem. While this conduct occurred at a board meeting rather than BRC, we would expect a similar level of active oversight by the BRC.

Better practice |

Asking questions of management is good practice. But simply expressing concern, or passively providing feedback for management’s ‘consideration’, is not the same as genuine active oversight. Such oversight can involve changing behaviours and imposing consequences, where necessary. This is especially so where the board or BRC sees evidence of systemic issues (for instance, the continued failure of internal controls that result in not seeking board approval).[43]

We did observe instances of boards providing active oversight:

- One company introduced a requirement that accountable executives from the responsible business unit attend board meetings to talk to high-rated ‘red’ risk incidents and to take responsibility for closing them out.

- Where the board expressed concern over a particular course of action, we also observed an example of members asking specific questions about methodology, managing consequences and the adequacy of resourcing before requesting updates on progress and changes to reporting.

Boards should ask themselves:

|

Are we demonstrating active oversight of, and engagement with, matters being put to the BRC? Do we require management to act where we are not satisfied with what is being presented or recommended to the board? |

5 There should be clear escalation processes for urgent material risks

There should be clear and effective processes to escalate and deal with urgent material risks that arise between BRC meetings. Dealing in an ad hoc manner with time-sensitive issues that are sufficiently material to be escalated to the BRC can result in:

- no consistency in the matters escalated

- fractured information flows to the board

- board members only partially participating in significant decisions

- issues not being followed up appropriately.

The charter of one BRC set out a procedure for addressing time-sensitive issues arising between BRC meetings, which listed possible alternative decision makers and how the BRC would be notified. Nevertheless, ASIC observed that this company adopted alternate practices in some instances, such as the board Chair calling all board members to discuss a matter.

In fact, we observed different practices adopted within companies and between companies in response to urgent risks, including:

- discussions between the CRO and the BRC chair. In some cases BRC chairs would then notify the remaining BRC members by phone or email. The matter may also be placed on the agenda of the next BRC

- direct communication between the CEO and board chair

- impromptu board or BRC meetings

- in the absence of a BRC meeting, escalation of urgent issues to the next monthly full board meeting

- for urgent risk matters arising through an audit, impromptu discussions between the board audit committee chair, board chair, BRC chair and CEO.

The variety of processes within and between companies indicates there is no standard process for escalating urgent material risks – either within each company, or across the financial services industry.

Better practice |

Different circumstances may warrant different responses. What is important is that there should be transparent and consistent processes for escalating urgent material risks outside committee meetings. These should detail who, where and how to deal with and close out these issues.

Transparent escalation processes should define:

- who to escalate the matter to initially (the BRC chair, the CEO and/or the board chair)

- the forum for addressing the issue and how to involve BRC members (for example, hold an ad hoc BRC meeting or full board meeting, or have the BRC chair and CRO reach a decision, which is then communicated to other BRC members)

- how issues are recorded and closed out so the BRC retains oversight if these matters will not be captured in the action items register of regular committee meetings.

Boards should ask themselves:

|

Do we have transparent and effective processes for escalating urgent material to the board? Are these processes followed consistently? |

6 Emerging issue: Implications of changing BRC membership and attendance patterns

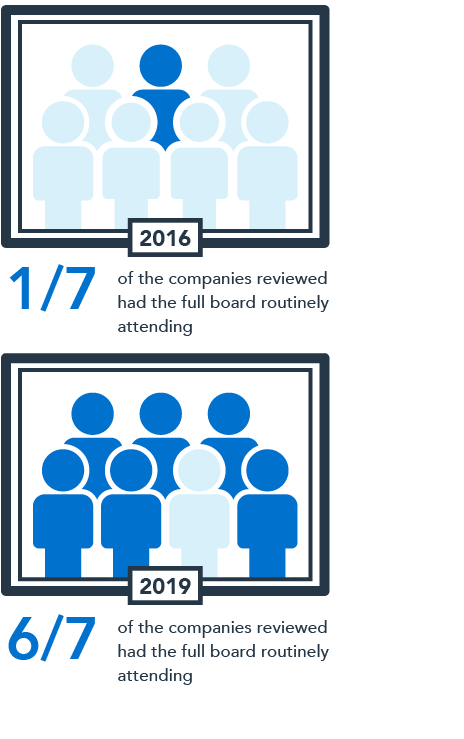

We observed an emerging trend in which all non-executive directors are increasingly invited to BRC meetings (see infographic below). While in two of the six companies all non-executive directors were members of the BRC, we observed that in six of the seven companies all non-executive directors routinely attended BRC meetings.

BRC attendance

Interviewees noted that having full board attendance had advantages:

- There was less need to repeat issues to the full board.

- Nothing was ‘lost in translation’ as all directors were informed about all areas, helping them make other general board decisions.

- It freed up the full board to focus on strategy.

Some interviewees cited disadvantages:

- Having all directors in the room stifled conversations and did not allow deep dives into topics because there were too many voices.

- Full board attendance was likely to lead to a ‘good news culture’ in reporting as ‘the better the audience, the better the news’.

Where all non-executive directors attend BRC meetings, there are potential unintended consequences, such as a lack of voting rights for directors who are not members.

Better practice |

Companies with full board attendance at BRC meetings should consider their motivations for establishing such a practice. If a company has inefficient information flows, resulting in the full board having to attend BRC meetings, the company should also prioritise improving its processes.

Where a company decides to have all directors attend BRC meetings, it would be better practice to formalise this decision by making all directors committee members. This would ensure that attending directors have the requisite voting rights, so they are not disenfranchised from material risk decisions.

Formalising membership also reduces the risks involved with informally reducing information flows to the full board in circumstances where directors may stop attending BRC meetings at any time.

It is also essential for companies to have an effective BRC chair who retains control and carriage of BRC meetings. This is more likely to maintain structured and robust decision-making frameworks and accountabilities, regardless of membership and attendance.

Boards should ask themselves:

|

Are all board members (whether or not they are formal members of the BRC) fully informed, and do they have an opportunity to participate and be heard on risks? Is the BRC the right size to be effective? Does the BRC’s charter accurately reflect the BRC’s actual practice? |

International trends |

In the United Kingdom, large listed companies are required to establish a BRC that takes primary responsibility for risk management. In other prominent international jurisdictions, risk committees are also gaining traction outside financial services.

In relation to boards and board committees holding management to account, the Canadian regulator expects financial institutions to provide evidence in meeting minutes that boards are effectively challenging management. While this has led to more rigorous documenting of challenges, it is also likely to focus the board’s attention on ensuring that effective challenge occurs.

Globally, first-line business units (in the three lines of defence model) are increasingly participating in, owning and being held accountable at board level for risk management. Many entities are reviewing and refining their governance structures, focusing on the first line presenting the business unit’s risk profile to the board, rather than the second line (the risk function) performing this task.

39 This data is accurate as at 1 September 2019.

40 OECD Corporate Governance Factbook 2019, 11 June 2019, page 124.

41 See Attachment A at page 5 for discussion regarding reflective thinking time.

42 Items requiring a decision included items for approval. ‘Non-decision items’ included items for noting, discussion and consideration. The review did not measure the number of times the same matter was brought before the BRC.

43 See Attachment A at page 4 for discussion regarding boards challenging management.